How Hurricane Helene Devastated Western North Carolina

CEE Distinguished Professor Auroop Ganguly and MES/CEE Associate Professor Samuel Muñoz explain how the devastating effects of Hurricane Helene reached parts of western North Carolina, an area ordinarily unaffected by extreme weather patterns.

This article originally appeared on Northeastern Global News. It was published by Cynthia McCormick Hibbert. Main photo: Heavy rain caused by Hurricane Helene transformed western North Carolina from a reputed ‘climate haven’ to a disaster area, as shown here near Lake Lure. Photo by Melissa Sue Gerrits/Getty Images

From ‘climate haven’ to disaster zone: How Hurricane Helene became the perfect storm to devastate western North Carolina

Before the aftermath of Hurricane Helene dumped more than 30 inches of rain on some parts of western North Carolina and led to historic flooding that has killed more than 30 people in the mountainous region, Asheville was known as a “climate haven.”

News reports say people were moving to the city that houses the historic Biltmore Estate to escape extreme heat in the summer, sea level rise, and hurricanes.

The mudslides and floods that have swept away children and their grandparents and others in the foothills and mountains of North Carolina were a risk that few saw as imminent, say Northeastern University professors Auroop Ganguly and Samuel Munoz.

The catastrophe, says Ganguly, distinguished professor of civil and environmental engineering, is an example of a “gray swan” event.

Gray swans happen when “places not thought to be at risk may not be immune anymore to the ravages of weather extremes that are relatively ‘unprecedented’ in the region,” he says.

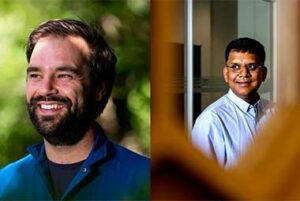

Professors Samuel Munoz and Auroop Ganguly say when Helene slammed into North Carolina’s mountains it unleashed a perfect storm of flooding and infrastructure collapse. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University and Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

The path of Hurricane Helene from landfall as a Category 4 hurricane in the Big Bend region of Florida’s Gulf coastline to western North Carolina was “fairly unusual,” says Munoz, associate professor of marine and environmental sciences at Northeastern’s Marine Science Center.

But Helene itself packed unusual strength, landing Thursday night with 140-mph winds and creating a massive storm surge.

“The biggest thing is that this hurricane had a lot of forward speed and momentum, which means that it moved inland,” Munoz says.

“Usually a hurricane hits land and then very quickly fizzles out,” he says. That was not the case for Helene.

It barrelled up into the Appalachian mountains, where its moisture was forced up into cooler air and rapidly condensed.

“You had moisture-laden air hitting a mountain range, and that produced a lot of rain,” Munoz says. Visualize the storm as a water-soaked sponge hitting a wall, he says. “You’re squeezing out a lot of moisture quickly.”

While research is still underway on the exact ways climate change is affecting hurricanes, there is scientific consensus that warmer water and air temperatures mean that hurricanes will produce more precipitation, Munoz says.

Read Full Story at Northeastern Global News